A Brief History of the 13 Original Colonies

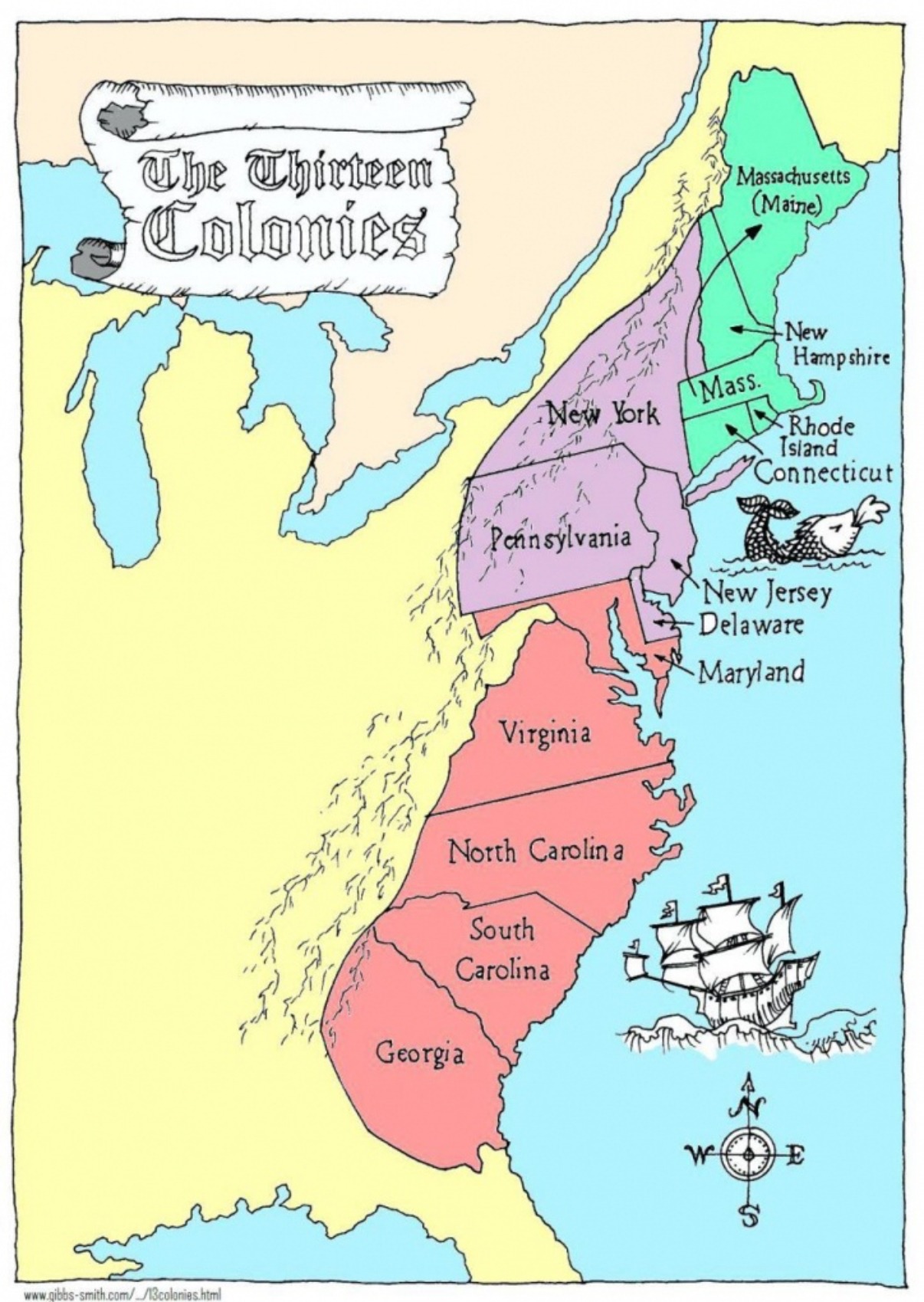

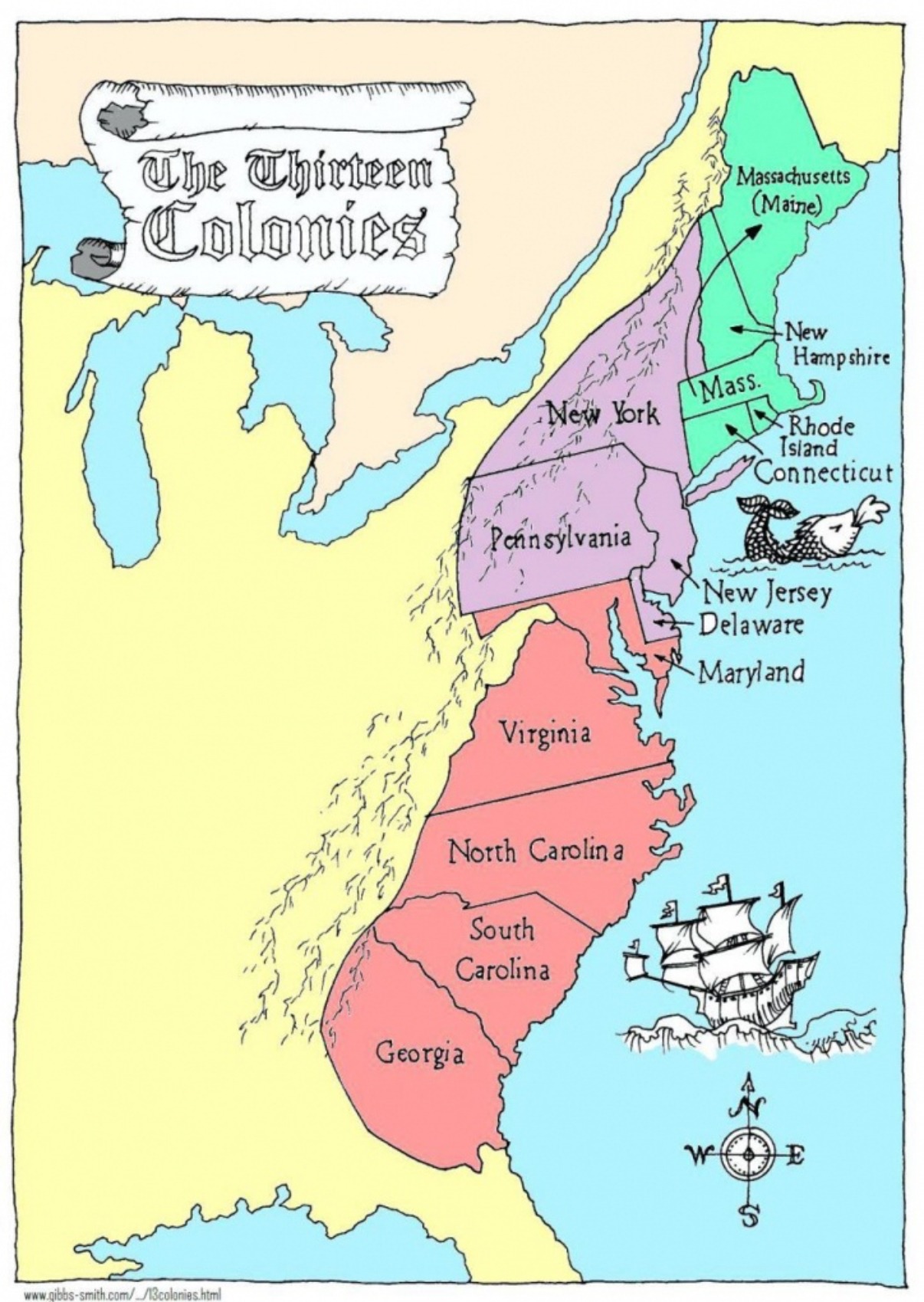

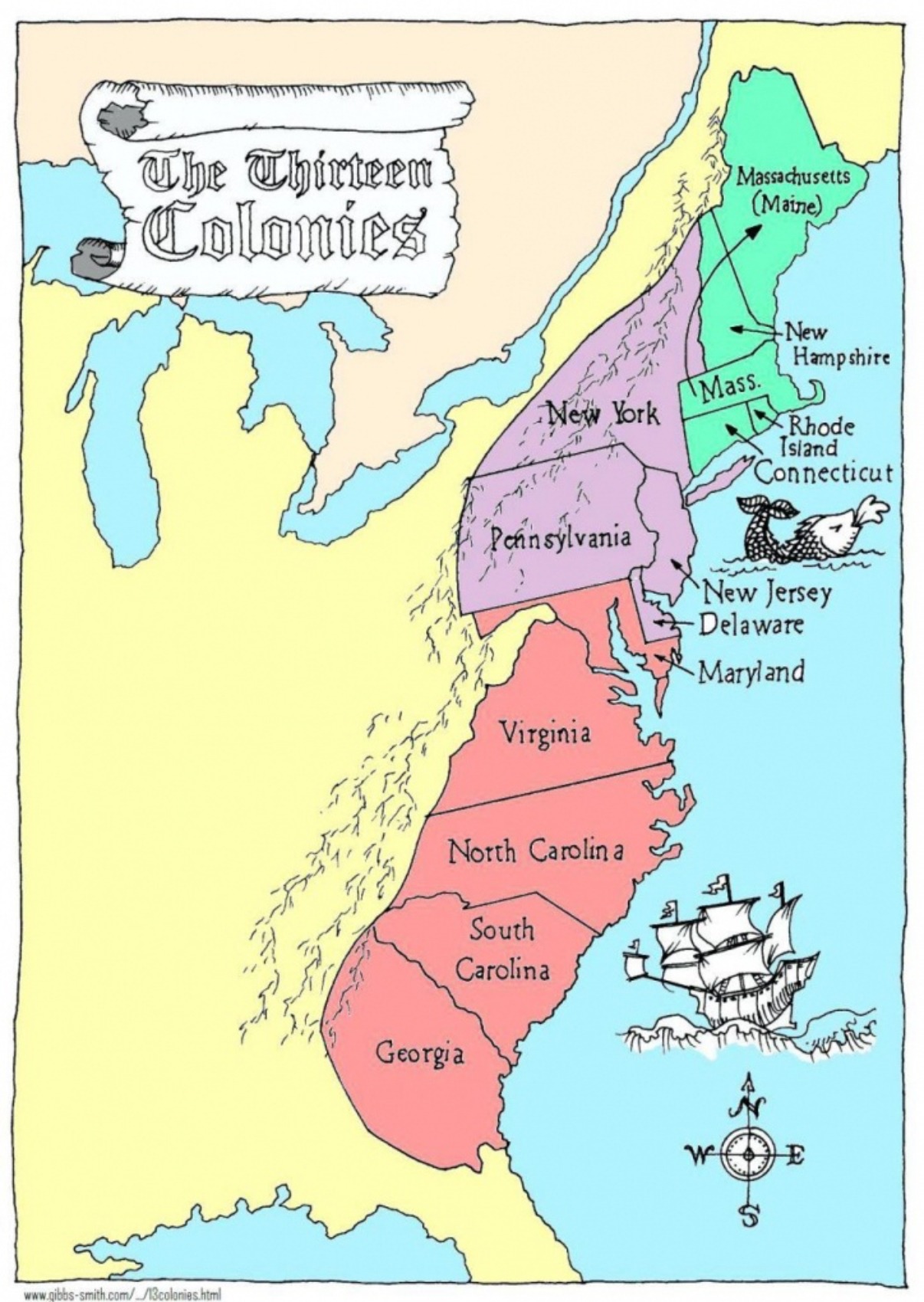

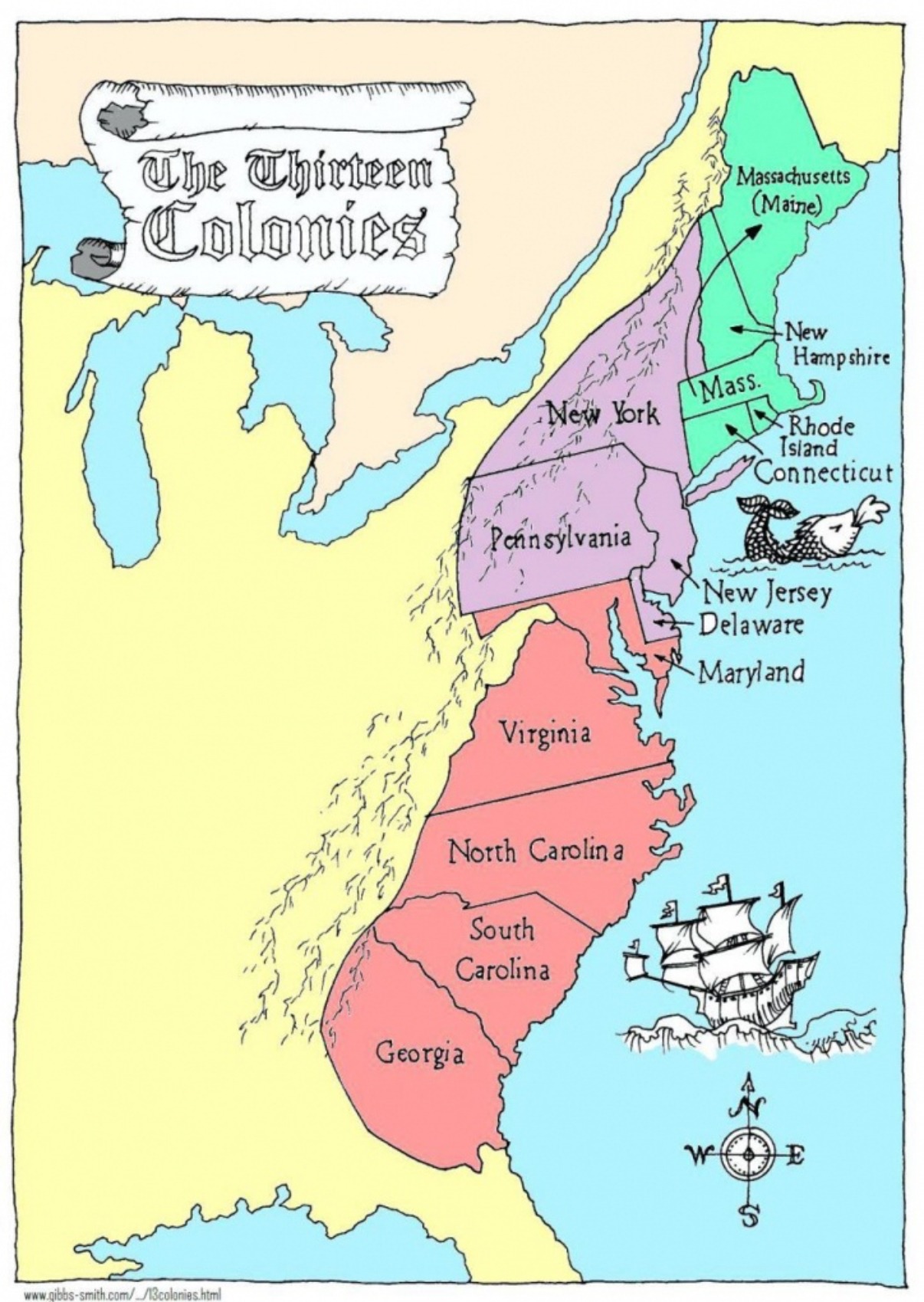

The 13 original American colonies were established by European settlers, primarily from England, along the Atlantic coast of North America between the early 17th and mid-18th centuries:

The story begins with Virginia, the first permanent English colony, founded in 1607 at Jamestown. Sponsored by the Virginia Company, settlers faced harsh conditions—disease, starvation, and conflicts with Indigenous peoples—but tobacco cultivation eventually brought economic stability. In 1620, Plymouth Colony (later part of Massachusetts) was established by the Pilgrims, religious separatists seeking freedom from persecution. The nearby Massachusetts Bay Colony, founded in 1630 by Puritans, grew into a theocratic society centered on trade, fishing, and farming.

KING CHARLES I

KING OF ENGLAND (Reigned 1625-1649)

Maryland emerged in 1634 as a haven for English Catholics, granted by King Charles I to the Calvert family, though it also attracted Protestant settlers. Connecticut (1636) and Rhode Island(1636) splintered from Massachusetts, driven by religious dissenters like Thomas Hooker and Roger Williams, who prioritized individual liberty and separation of church and state.

THOMAS HOOKER (RELIGIOUS DISSENTER)

ROGER WILLIAMS (RELIGIOUS DISSENTER)

The Carolinas were chartered in 1663, splitting into North Carolina and South Carolina by 1712. These colonies thrived on rice, indigo, and later slavery, with South Carolina developing a plantation elite. New Hampshire, initially tied to Massachusetts, became a separate colony in 1679, focusing on timber and fishing.

New York began as New Netherland, a Dutch colony, until the English seized it in 1664, renaming it after the Duke of York. Neighboring New Jersey, also carved from Dutch territory, was established as a proprietary colony in 1664, later splitting into East and West before reuniting as a royal colony in 1702.

Pennsylvania, founded in 1681 by William Penn as a Quaker refuge, promoted religious tolerance and fair dealings with Native Americans, attracting diverse settlers. Its offshoot, Delaware, originally part of New Sweden, became a separate colony in 1704 under Penn’s charter

A Brief History of the 13 Original Colonies

The 13 original American colonies were established by European settlers, primarily from England, along the Atlantic coast of North America between the early 17th and mid-18th centuries:

The story begins with Virginia, the first permanent English colony, founded in 1607 at Jamestown. Sponsored by the Virginia Company, settlers faced harsh conditions—disease, starvation, and conflicts with Indigenous peoples—but tobacco cultivation eventually brought economic stability. In 1620, Plymouth Colony (later part of Massachusetts) was established by the Pilgrims, religious separatists seeking freedom from persecution. The nearby Massachusetts Bay Colony, founded in 1630 by Puritans, grew into a theocratic society centered on trade, fishing, and farming.

Maryland emerged in 1634 as a haven for English Catholics, granted by King Charles I to the Calvert family, though it also attracted Protestant settlers. Connecticut (1636) and Rhode Island (1636) splintered from Massachusetts, driven by religious dissenters like Thomas Hooker and Roger Williams, who prioritized individual liberty and separation of church and state.

The Carolinas were chartered in 1663, splitting into North Carolina and South Carolina by 1712. These colonies thrived on rice, indigo, and later slavery, with South Carolina developing a plantation elite. New Hampshire, initially tied to Massachusetts, became a separate colony in 1679, focusing on timber and fishing.

New York began as New Netherland, a Dutch colony, until the English seized it in 1664, renaming it after the Duke of York. Neighboring New Jersey, also carved from Dutch territory, was established as a proprietary colony in 1664, later splitting into East and West before reuniting as a royal colony in 1702.

Pennsylvania, founded in 1681 by William Penn as a Quaker refuge, promoted religious tolerance and fair dealings with Native Americans, attracting diverse settlers. Its offshoot, Delaware, originally part of New Sweden, became a separate colony in 1704 under Penn’s charter.

Finally, Georgia, the last of the 13, was founded in 1733 by James Oglethorpe as a buffer against Spanish Florida and a social experiment, initially banning slavery (until 1750) and offering land to debtors.

By the mid-18th century, these colonies—diverse in economy, religion, and governance—had grown distinct identities yet shared grievances against British rule, setting the stage for the American Revolution in 1775. Together, they formed the foundation of the United States.

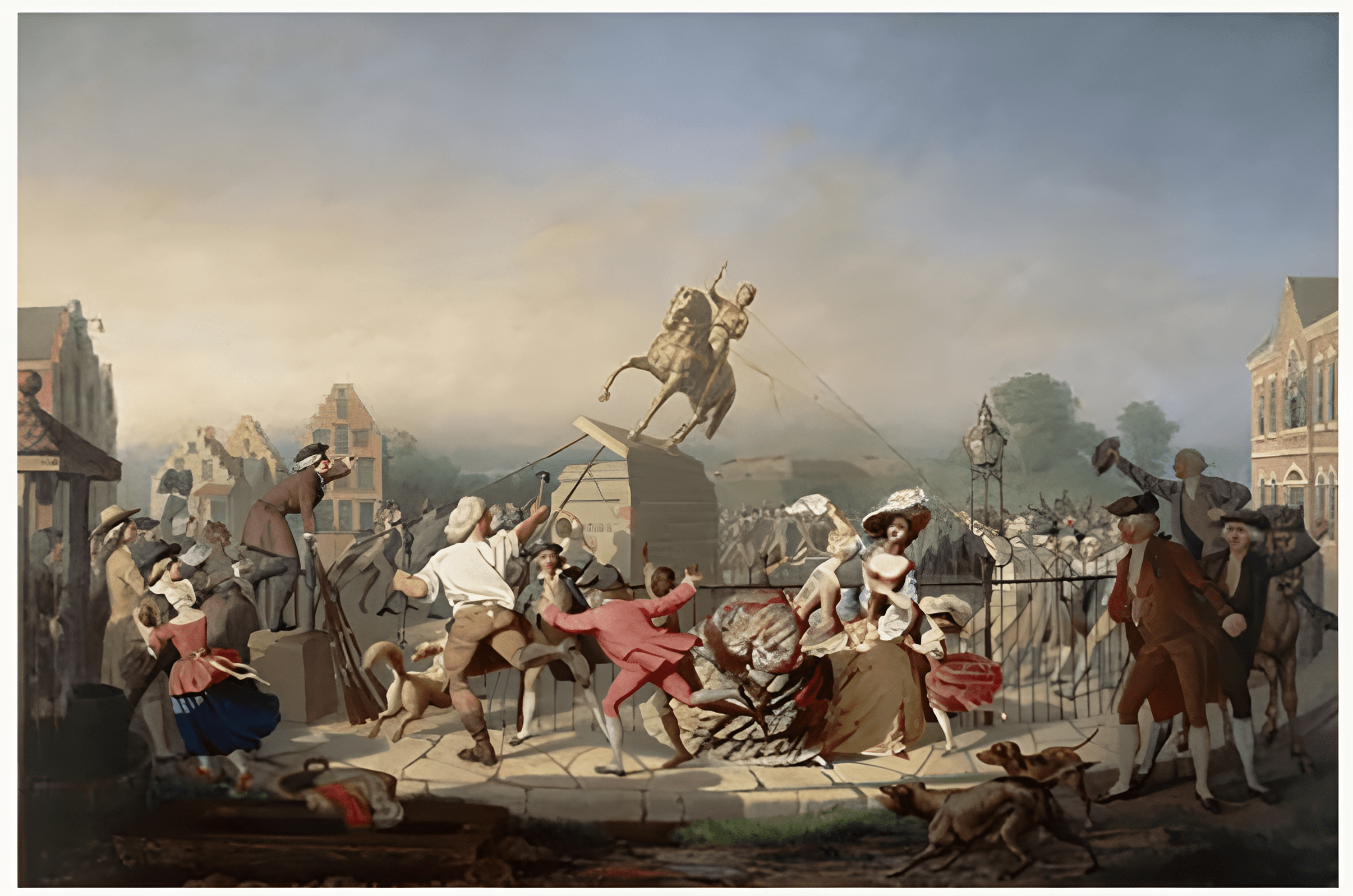

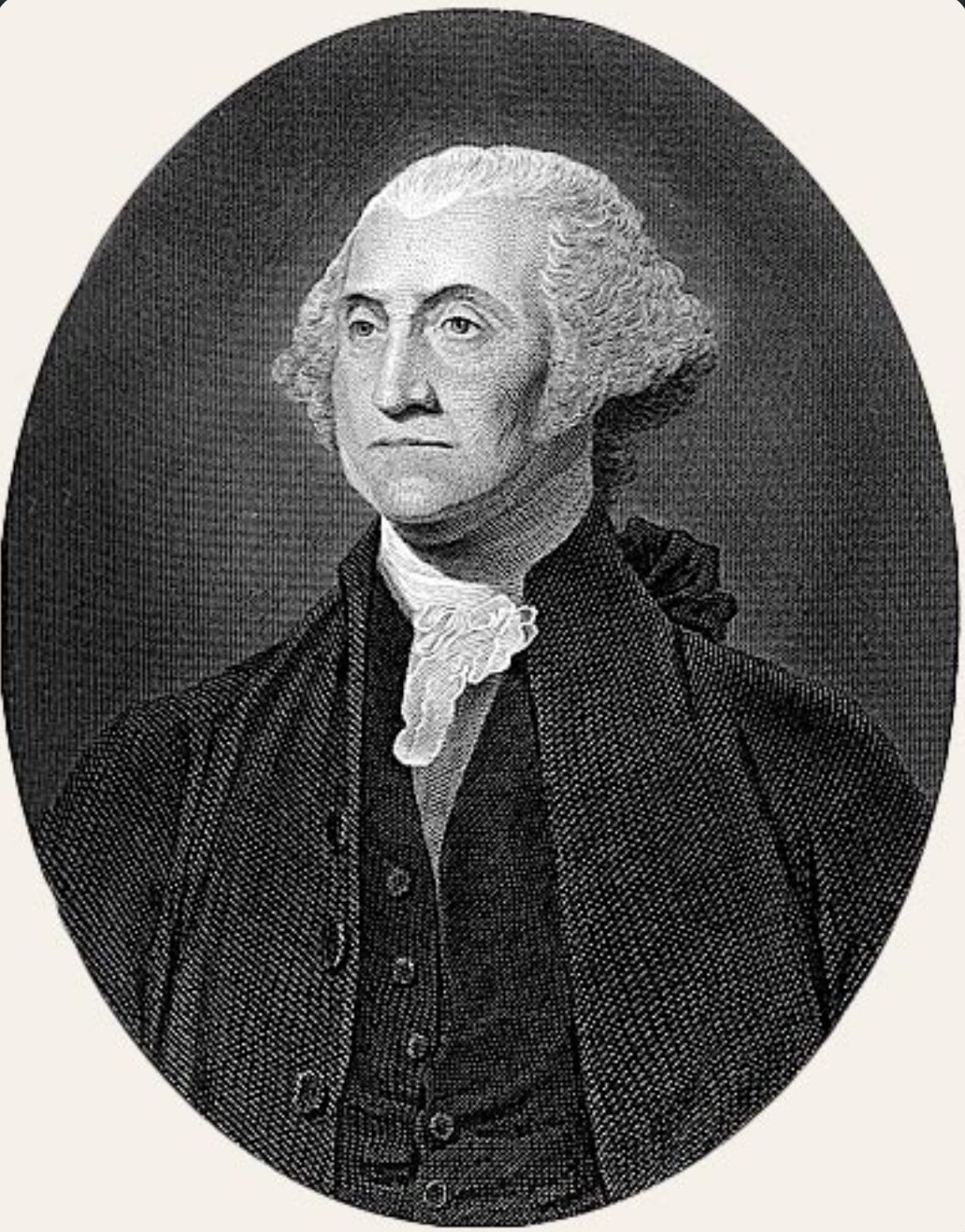

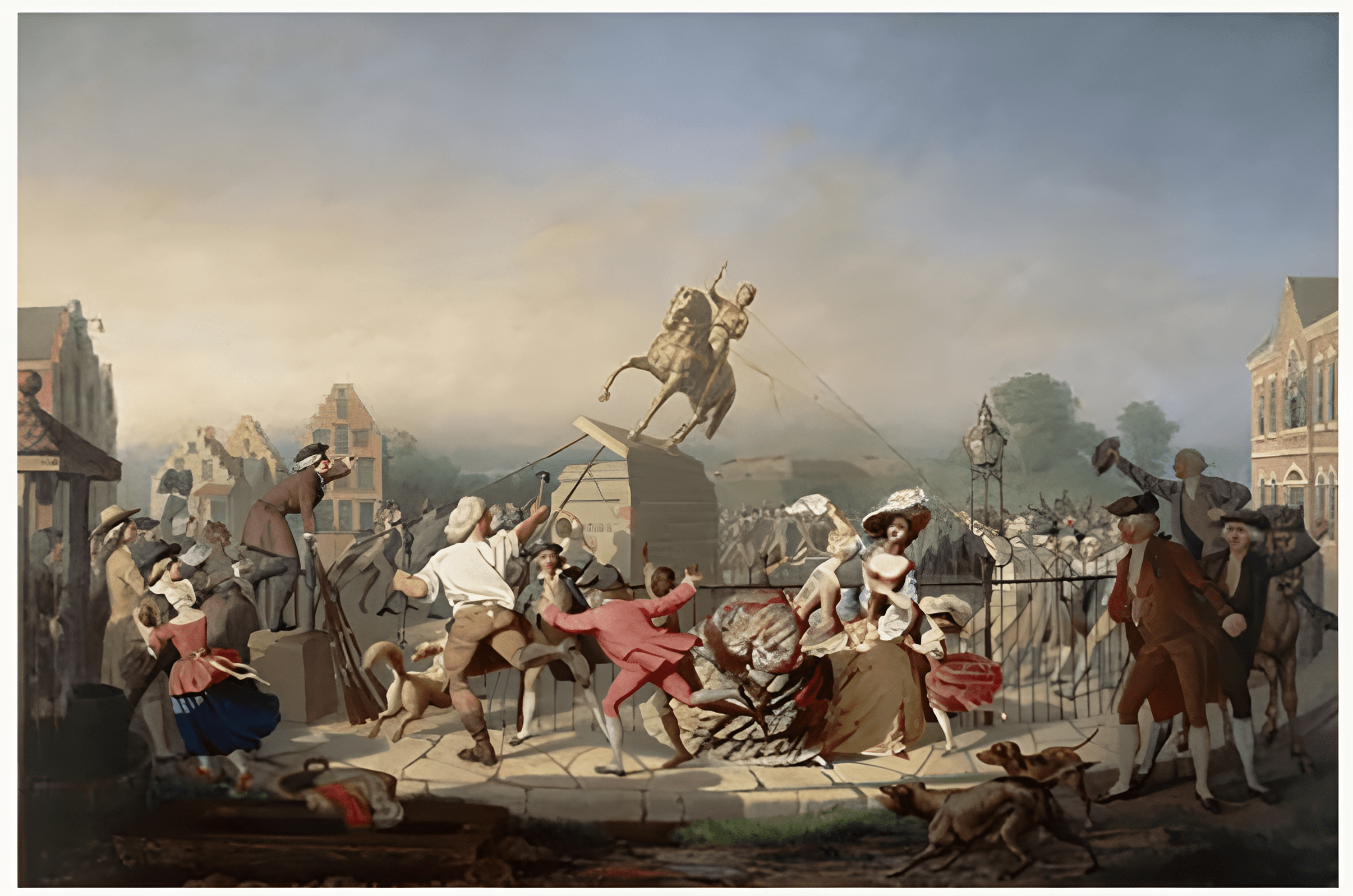

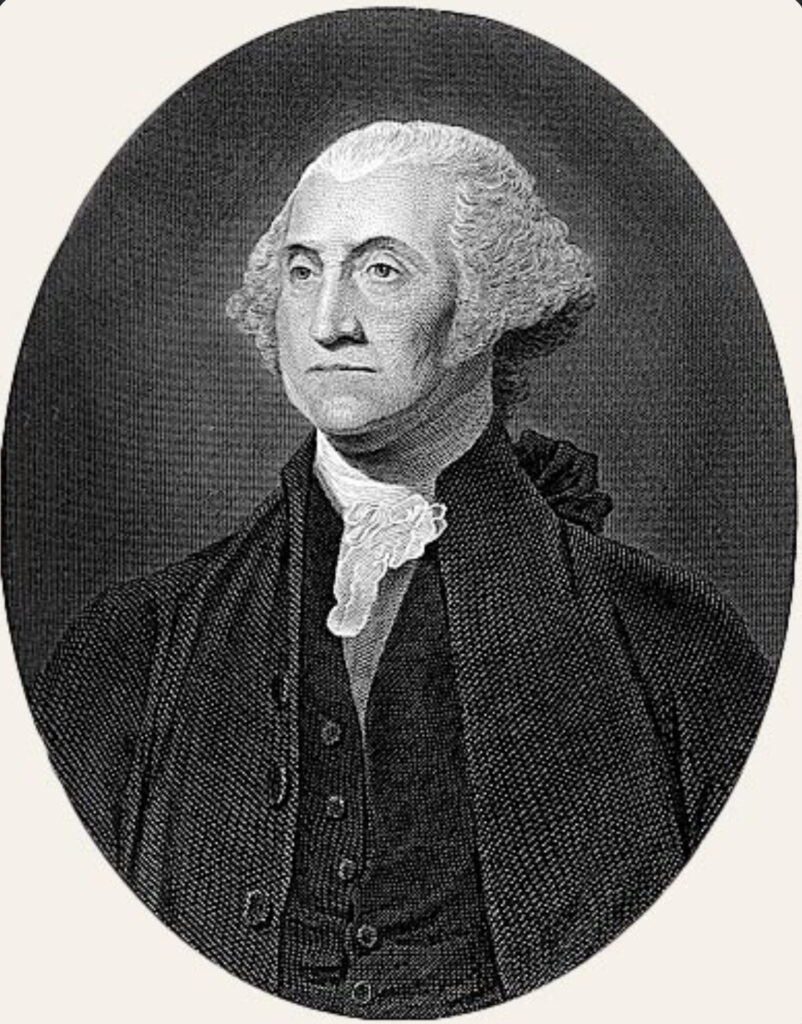

A Brief History of the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1775–1783) was a pivotal war where the thirteen American colonies fought for independence from British rule. It began with escalating tensions over taxation and governance, exemplified by acts like the Stamp Act and the Boston Tea Party, leading to armed conflict at Lexington and Concord in 1775. The Declaration of Independence, adopted in 1776, formalized the break from Britain. Under General George Washington, the Continental Army, bolstered by French support after the 1777 Saratoga victory, endured hardships like Valley Forge before triumphing at Yorktown in 1781. The 1783 Treaty of Paris secured U.S. sovereignty, establishing a new nation grounded in revolutionary ideals, though challenges like slavery persisted.

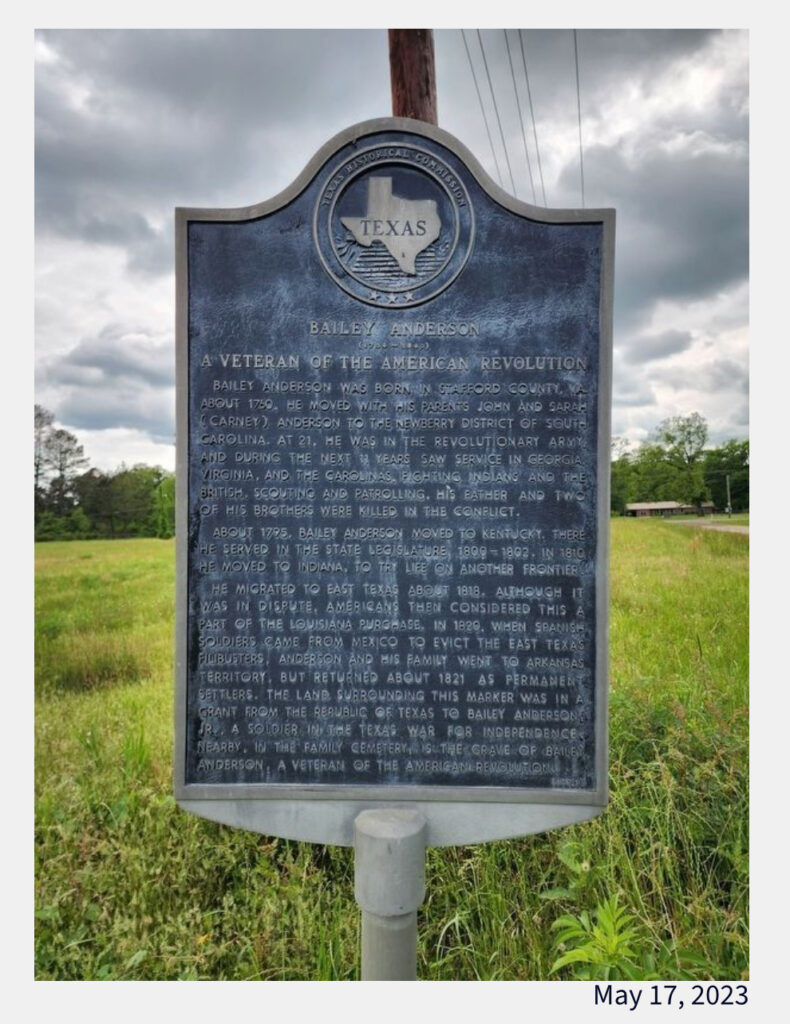

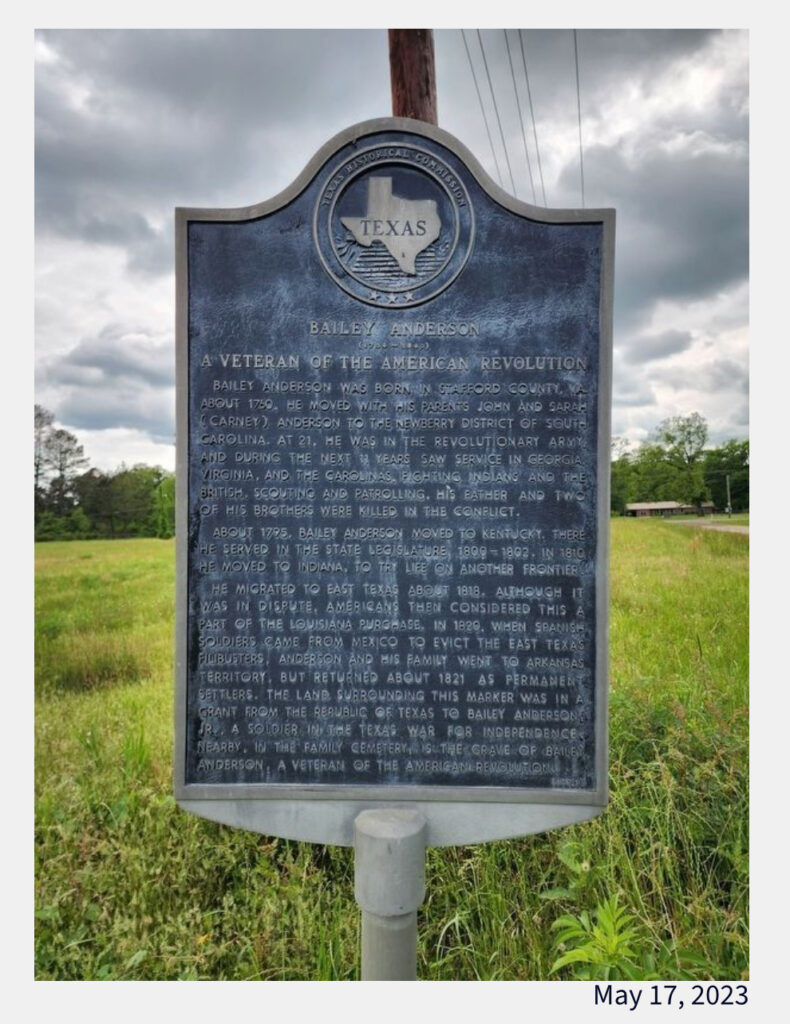

GEORGE WASHINGTON

Bailey Anderson, Sr. (1753–1840), born in Stafford County, Virginia, was a Patriot soldier and spy during the Revolution. Relocating to South Carolina’s Ninety Six District, he served in the militia with his father, John, and brothers, Scarlet and Joshua, all of whom perished in the war. Anderson participated in key southern battles—Musgrove’s Mill, Blackstocks, Ninety Six, and the Siege of Augusta—likely spying on British and Loyalist forces in the backcountry. After the war, he migrated to Kentucky (1795), served in its legislature (1800–1802), then moved to Indiana (1805), and finally settled in Texas by 1819. He died in Harrison County, Texas, in 1840, one of 46 Revolutionary War veterans buried there, honored with a Texas Historical Marker.

AUTHORS NOTE: Bailey Sanders, Sr., the owner of this website, Oak Cliff BBQ Company, and the creator of Prime Jerky Fries, is the 10th great grandson of this Revolutionary War patriot and Texas First Families pioneer. Bailey carried on the generations old family tradition of serving America, and is a Cold War and Persian Gulf War veteran. Bailey served first on the USS America (CV-66) conventional aircraft carrier, (at the time moored in Norfolk, Virginia), then on board the USS Von Steuben (SSBN-632) and USS Benjamin Franklin (SSBN-640), both FBM nuclear powered submarines (at the time as moored at Charleston Naval Submarine Base, Charleston, South Carolina), and later the USS Frank Cable (AS-40) submarine tender from April 1984 – December 1993.

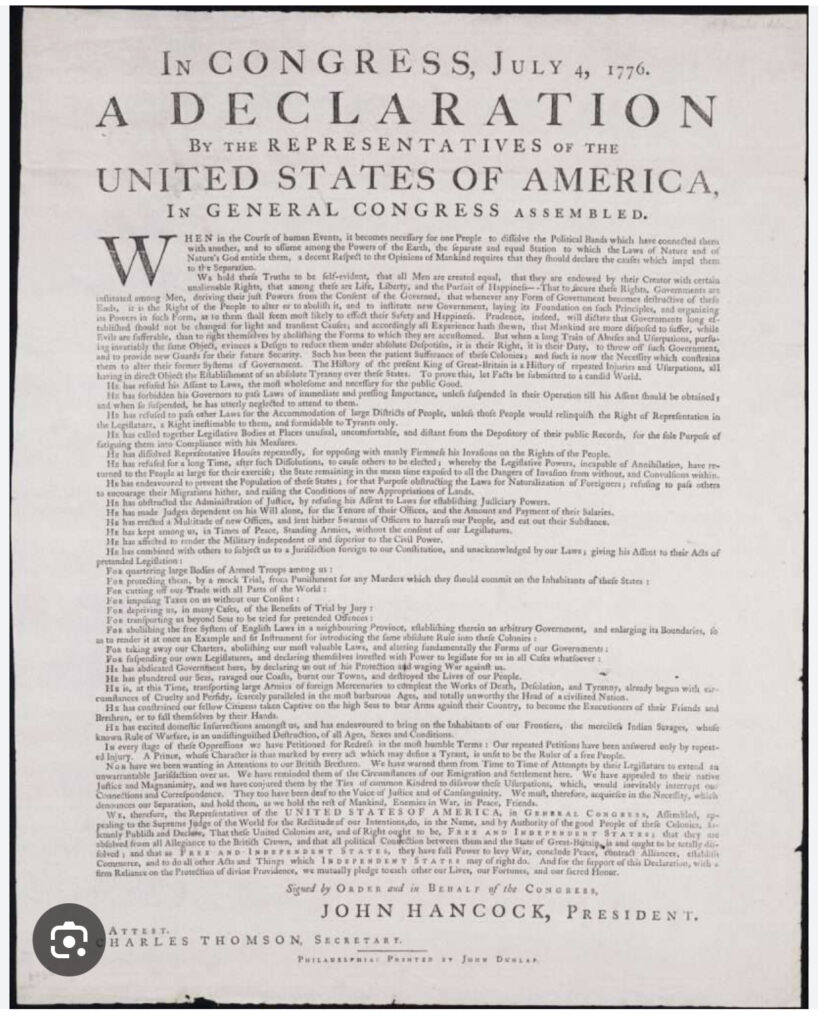

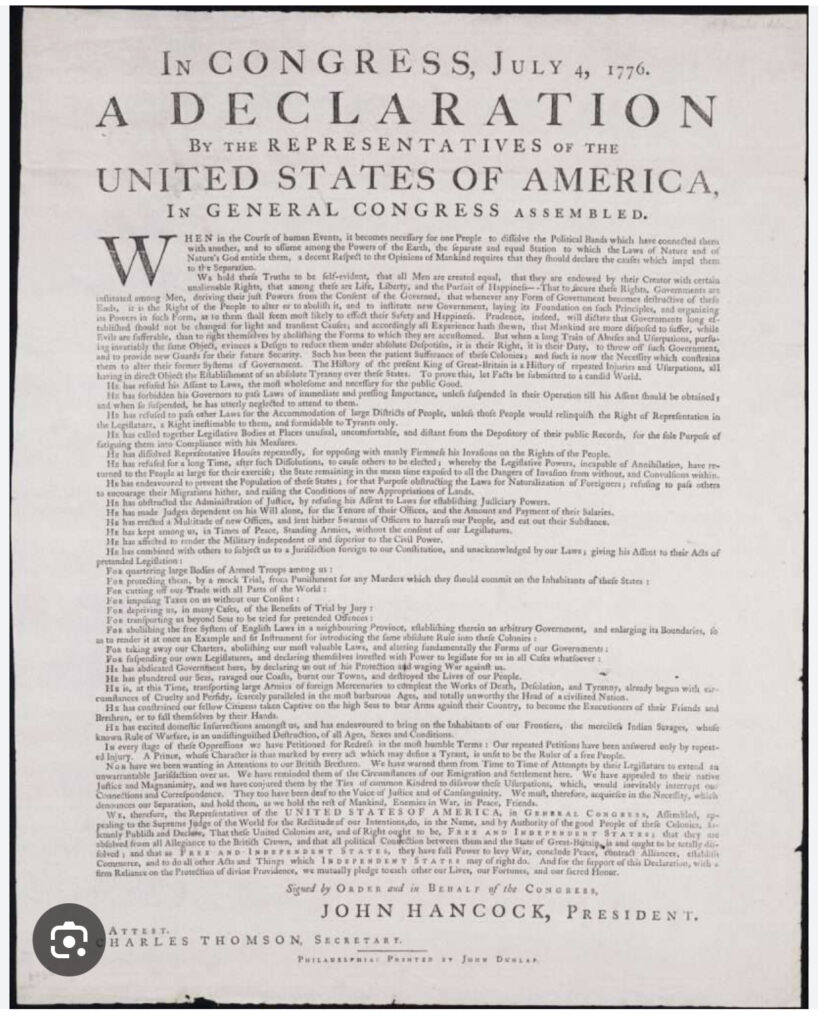

A Brief History of the Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence, adopted on July 4, 1776, by the Continental Congress, marked the formal assertion of the 13 American colonies’ break from British rule. Its history reflects the escalating tensions of the mid-18th century and the colonies’ push for self-governance.

By the 1760s, colonial resentment grew due to British policies like the Stamp Act (1765) and Townshend Acts (1767), which imposed taxes without colonial representation in Parliament. The Boston Massacre (1770) and Boston Tea Party (1773) intensified conflicts, leading to punitive measures like the Intolerable Acts (1774). In response, the First Continental Congress convened in 1774 to coordinate resistance, but war broke out in April 1775 with the battles of Lexington and Concord.

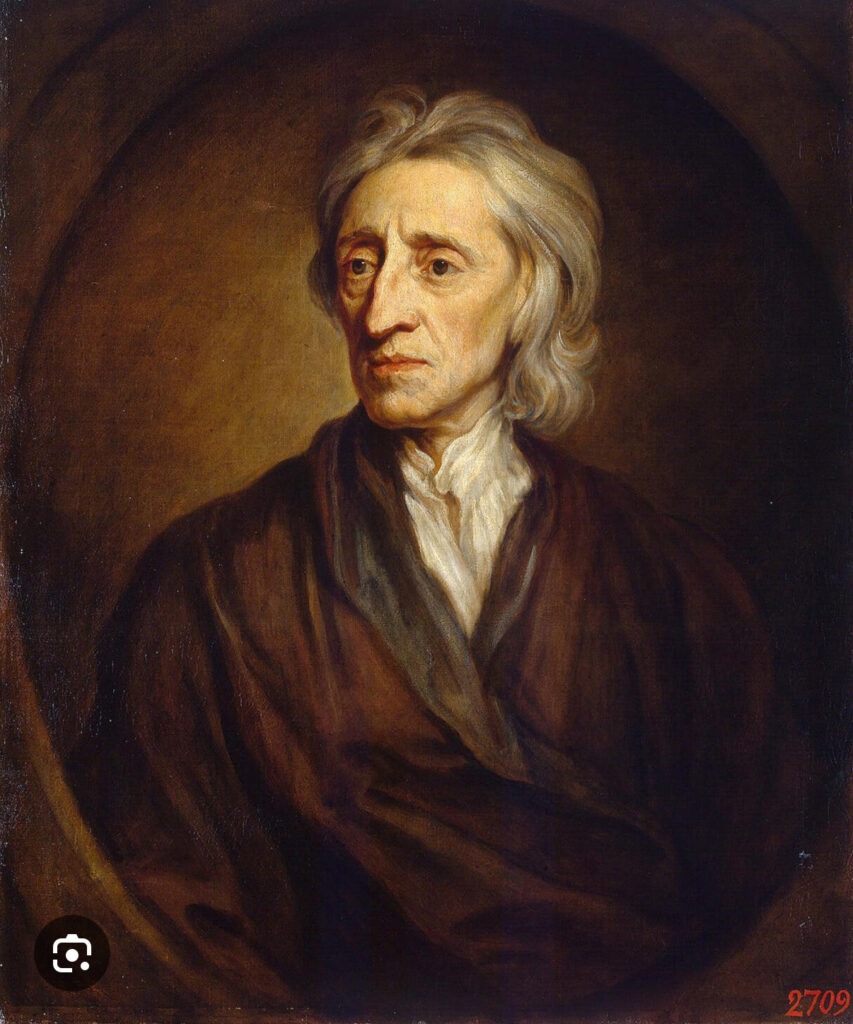

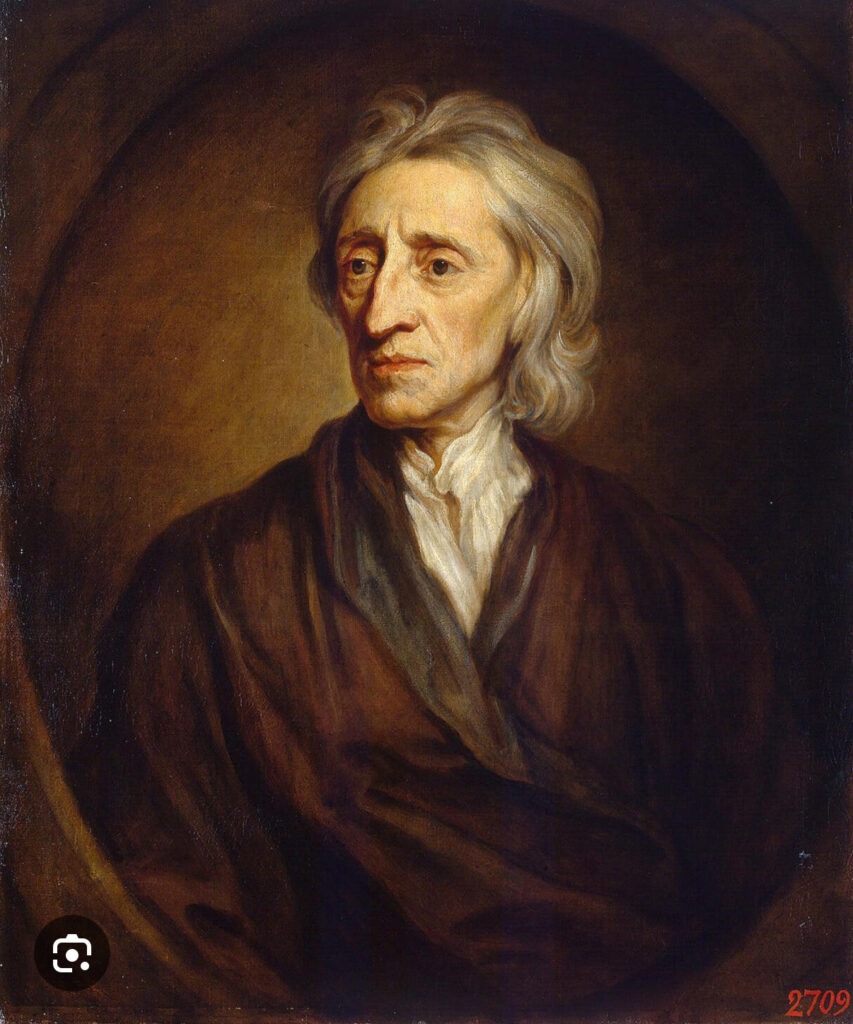

The Second Continental Congress, meeting in May 1775 in Philadelphia, initially sought reconciliation. However, King George III’s rejection of their Olive Branch Petition and his declaration of rebellion shifted sentiment toward independence. On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia proposed a resolution for independence, prompting Congress to appoint a committee—Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston—to draft a document. Jefferson, the primary author, completed the initial draft by late June, drawing on Enlightenment ideas from thinkers like John Locke, emphasizing natural rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

The draft underwent revisions, with Congress debating and editing it—most notably removing a passage condemning slavery—to unify the colonies. On July 2, 1776, Lee’s resolution passed, and on July 4, the final Declaration was adopted, signed initially by John Hancock, Congress president, and later by 56 delegates. Printed copies spread the news, with public readings igniting celebrations.

The Declaration didn’t end the war—it raged until 1783—but it defined the colonies as the United States, justifying their rebellion and rallying support. More than a legal document, it became a symbol of liberty, influencing democratic movements worldwide.

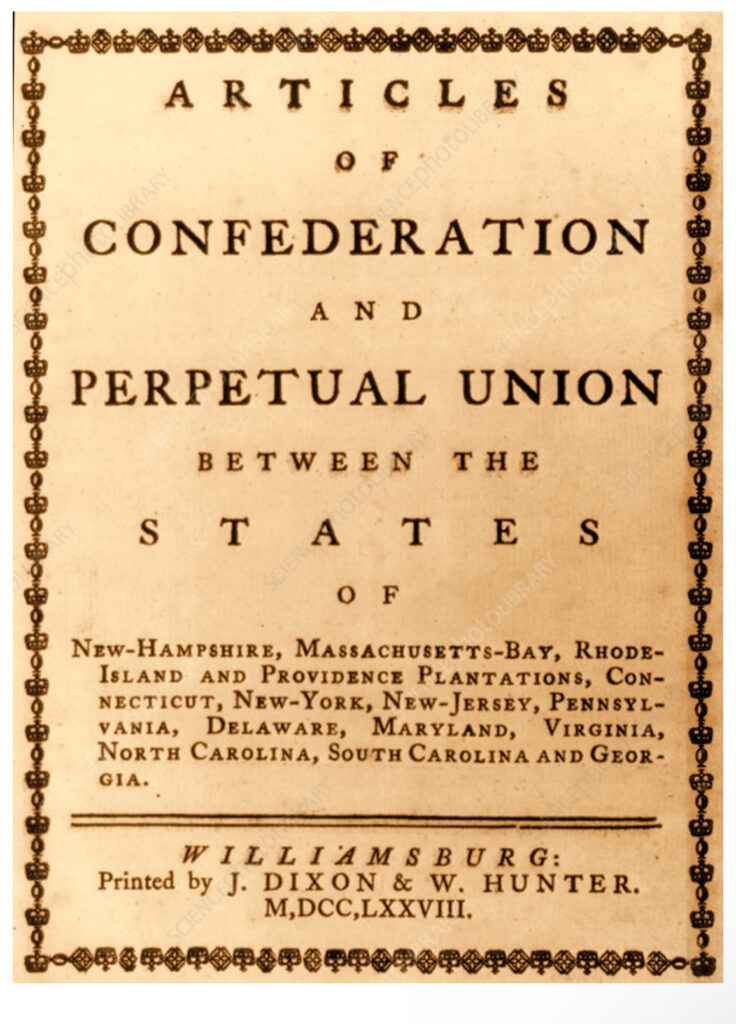

A Brief History of The Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation, America’s first constitution, were drafted and adopted during the Revolutionary War to unite the 13 colonies under a national government:

The Second Continental Congress began crafting the Articles in June 1776, shortly after declaring independence. John Dickinson of Pennsylvania led the effort, producing a draft by July 1776 that emphasized state sovereignty, reflecting fears of centralized power akin to British rule. After debate—particularly over western land claims and representation—the Articles were finalized and adopted on November 15, 1777. Ratification dragged on as states like Maryland held out, demanding Virginia cede its western territories. It was fully ratified on March 1, 1781, when Maryland signed, making it the governing framework of the “United States of America.”

JOHN DICKINSON

The Articles established a loose confederation, with a unicameral Congress as the central authority. Each state had one vote, regardless of size, and major decisions—like war or treaties—required nine of 13 votes. There was no executive or judicial branch, and Congress couldn’t tax directly or regulate commerce, relying on states for funds and enforcement. This structure aimed to preserve state autonomy while coordinating war efforts against Britain.

Initially, the Articles succeeded in managing the war, securing the 1783 Treaty of Paris, and passing the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which organized western territories and banned slavery there. However, weaknesses soon emerged. Without taxing power, the government faced chronic debt and couldn’t pay soldiers or creditors. Shays’ Rebellion (1786-1787), an uprising of Massachusetts farmers over economic woes, exposed the inability to maintain order or raise a militia swiftly.

TREATY OF PARIS MAP

NORTHWEST ORDINANCE MAP

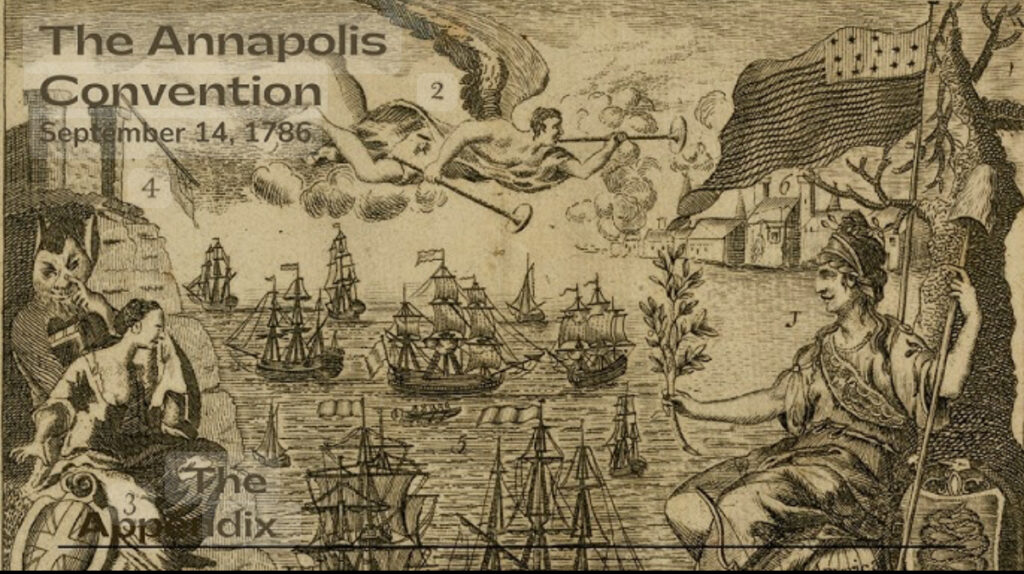

By 1787, these flaws—compounded by interstate trade disputes and a weak international presence—spurred calls for reform. The Annapolis Convention of 1786 proposed a new meeting, leading to the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. The Articles were abandoned for the stronger U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1788. In force for just a decade, the Articles highlighted the need for balance between state and federal power, shaping the nation’s enduring government.

THE ANNAPOLIS CONVENTION OF 1786

Watch this video for Lessons Learned from the Articles of Confederation:

The plight of African-Americans and a Brief History of Slavery in America:

Slavery in America began in the early 16th century when European settlers, particularly the Spanish and Portuguese, brought enslaved Africans to the New World to work in the colonies.

DEPICTION OF NEW WORLD SLAVE

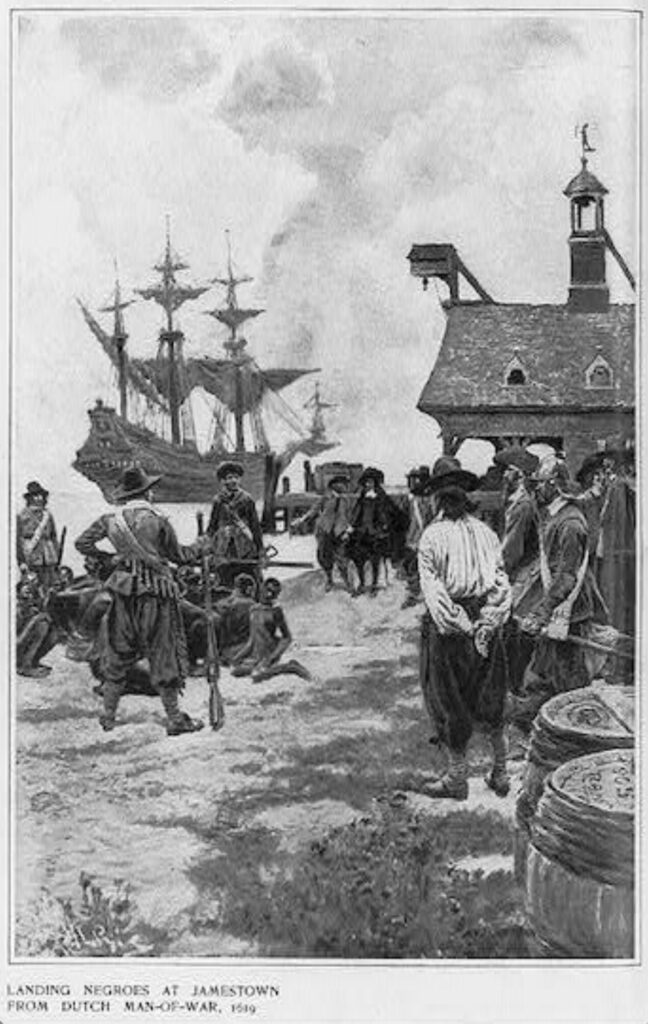

The first recorded arrival of Africans in British North America occurred in 1619, when the White Lion, a Dutch ship, brought 20 enslaved individuals to Jamestown, Virginia. Over the next two centuries, the transatlantic slave trade expanded dramatically, with millions of Africans forcibly transported to the Americas.

SLAVES LANDING AT JAMESTOWN

The trans-Atlantic slave trade was the largest long-distance forced movement of people in recorded history. From the sixteenth to the late nineteenth centuries, over twelve million (some estimates run as high as fifteen million) African men, women, and children were enslaved, transported to the Americas, and bought and sold primarily by European and Euro-American slaveholders as chattel property used for their labor and skills.

By the 18th century, slavery became a cornerstone of the Southern economy, particularly in tobacco, rice, and later cotton production, fueled by the invention of the cotton gin in 1793 by Eli Whitney.

ELI WHITNEY – INVENTOR (COTTON GIN)

MUTINY ON THE AMISTAD

(African-American History of 1839)

WATCH this short video about the revolt on the Amistad:

https://www.britannica.com/summary/Transatlantic-Slave-Trade-Timeline#/media/1/1913480/250810

AMISTAD

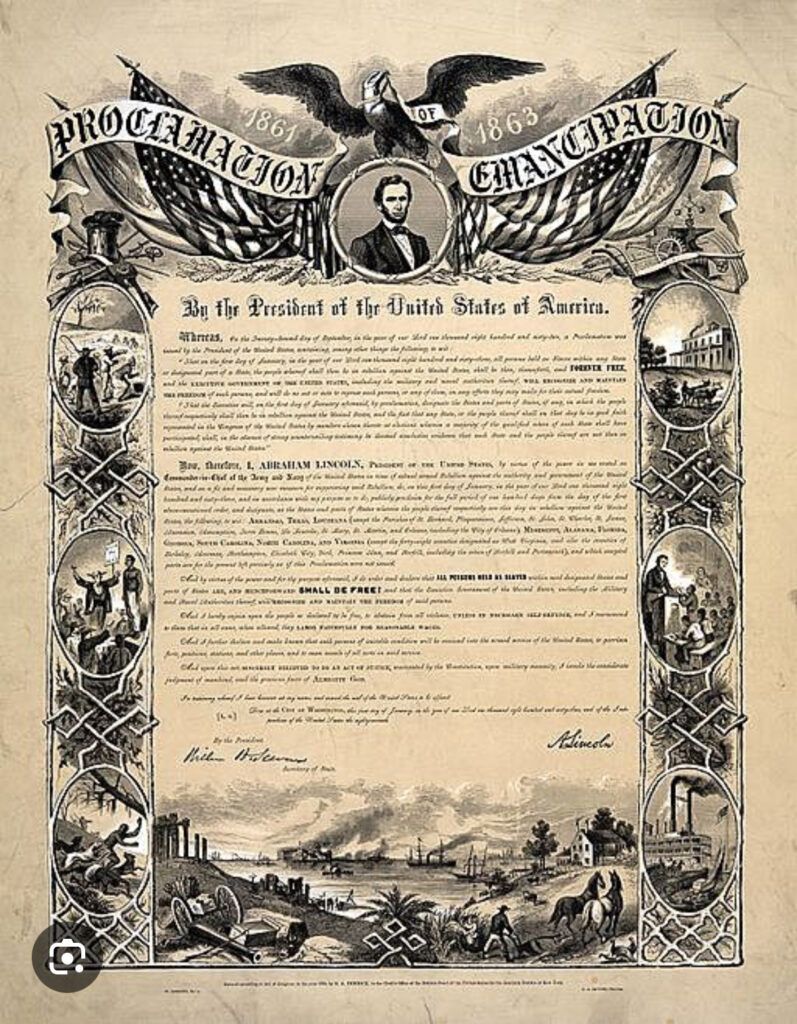

The U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1788, implicitly protected slavery through provisions like the Three-Fifths Compromise, counting enslaved people as three-fifths of a person for representation. Tensions over slavery grew as the nation expanded westward, culminating in the Civil War (1861–1865). The Union victory led to the Emancipation Proclamation (1863) by President Abraham Lincoln, freeing enslaved people in Confederate states, and the 13th Amendment (1865), abolishing slavery nationwide.

CIVIL WAR

EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION

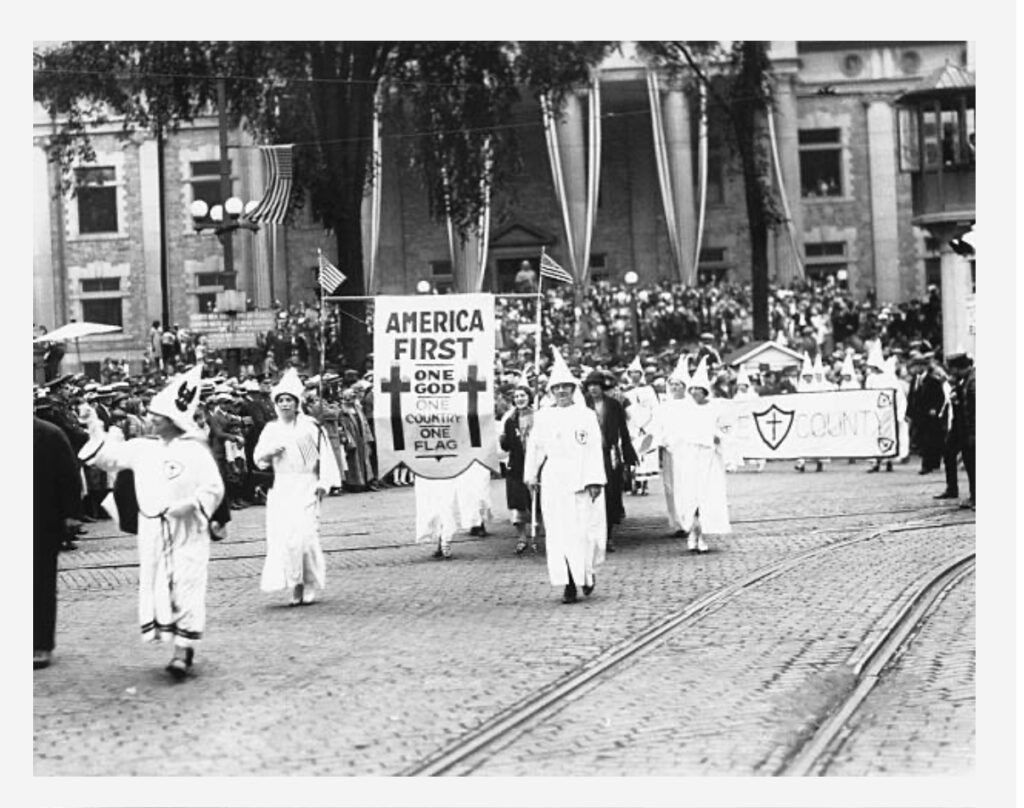

Despite abolition, racial oppression persisted through segregation. In the South, “Black Codes” and later Jim Crow laws (starting in the 1870s) enforced racial separation in public facilities, schools, and transportation. The 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision upheld “separate but equal,” legitimizing segregation. African Americans faced systemic discrimination, disenfranchisement via poll taxes and literacy tests, and widespread violence, including lynchings by groups like the Ku Klux Klan.

SEGREGATED CLASSROOM

KKK MARCH

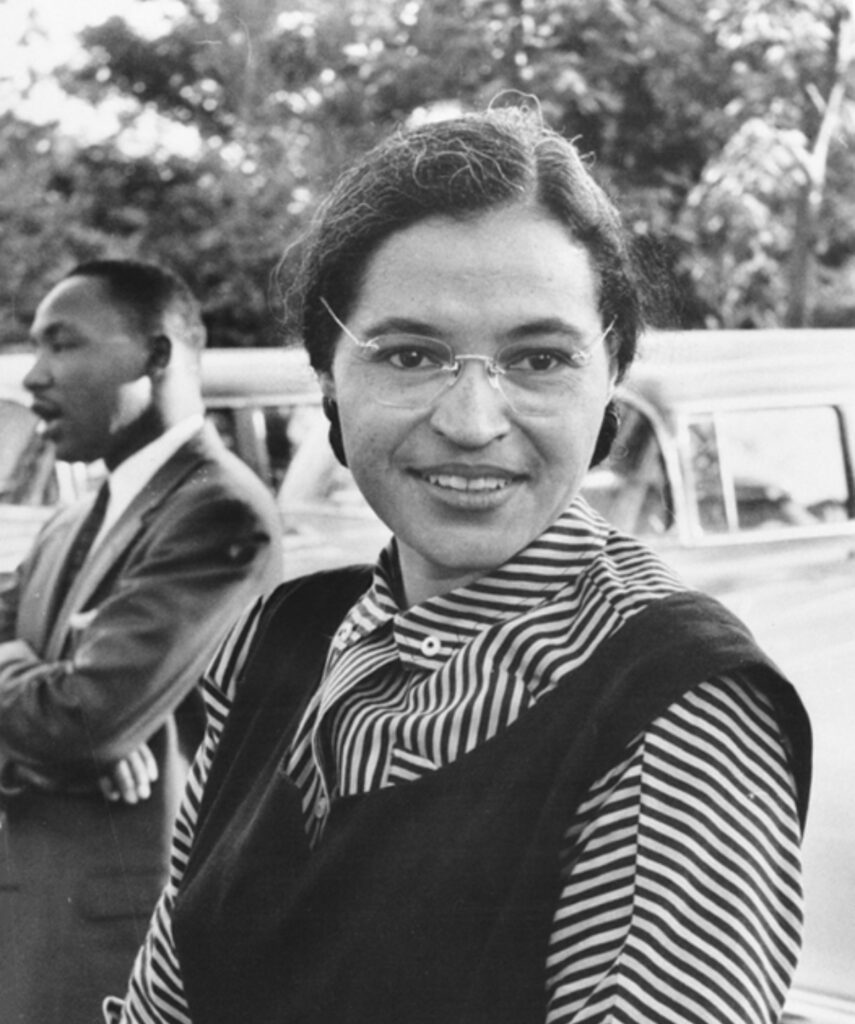

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s challenged this status quo. Key events included the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling, declaring segregated schools unconstitutional, and the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott sparked by Rosa Parks. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. emerged as a leader, advocating nonviolent resistance.

ROSA PARKS

DR MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed segregation in public places and employment discrimination, followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which dismantled barriers to Black voting. These laws marked the legal end of segregation, though their full implementation and societal impact unfolded over decades.

PROTEST FOR CITIZENSHIP

The post-Civil Rights era (1965–present) marked significant progress and ongoing challenges for African Americans. After the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawed racial discrimination and protected voting rights, African Americans gained greater access to education, employment, and political participation. The Black Power movement (mid-1960s–1970s), led by figures like Malcolm X and the Black Panthers, emphasized Black pride, self-defense, and economic independence, shifting focus from integration to empowerment.

Politically, African Americans made historic strides: Thurgood Marshall became the first Black Supreme Court Justice in 1967, Shirley Chisholm the first Black woman in Congress in 1968, and Barack Obama the first Black president in 2008. Economically, the Black middle class grew, with Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) playing a key role. By 2019, African Americans owned over 1.5% of national wealth, up from 0.5% in 1863, though disparities persisted.

However, racial issues remained. The War on Drugs (1980s–1990s) and crack cocaine epidemic disproportionately impacted Black communities, contributing to mass incarceration—African Americans made up 38% of the U.S. prison population in 2023 despite being 13% of the population. Redlining and discriminatory practices limited housing and wealth accumulation. The Black Lives Matter movement, sparked in 2013, highlighted ongoing police violence and racial inequity, with high-profile cases like those of Eric Garner and Michael Brown fueling protests.

Culturally, African Americans shaped global trends through the Black Arts Movement, hip-hop, and figures like Oprah Winfrey, the only Black billionaire on Forbes’ list for much of the early 2000s. The New Great Migration saw millions return to the South for economic opportunities in desegregated cities. Despite tremendous progress, racial disparities in poverty (18.8% for African Americans vs. 10.5% overall in 2020) remain.

A Brief History of the 13 Original Colonies

The 13 original American colonies were established by European settlers, primarily from England, along the Atlantic coast of North America between the early 17th and mid-18th centuries:

The story begins with Virginia, the first permanent English colony, founded in 1607 at Jamestown. Sponsored by the Virginia Company, settlers faced harsh conditions—disease, starvation, and conflicts with Indigenous peoples—but tobacco cultivation eventually brought economic stability. In 1620, Plymouth Colony (later part of Massachusetts) was established by the Pilgrims, religious separatists seeking freedom from persecution. The nearby Massachusetts Bay Colony, founded in 1630 by Puritans, grew into a theocratic society centered on trade, fishing, and farming.

Maryland emerged in 1634 as a haven for English Catholics, granted by King Charles I to the Calvert family, though it also attracted Protestant settlers. Connecticut (1636) and Rhode Island (1636) splintered from Massachusetts, driven by religious dissenters like Thomas Hooker and Roger Williams, who prioritized individual liberty and separation of church and state.

The Carolinas were chartered in 1663, splitting into North Carolina and South Carolina by 1712. These colonies thrived on rice, indigo, and later slavery, with South Carolina developing a plantation elite. New Hampshire, initially tied to Massachusetts, became a separate colony in 1679, focusing on timber and fishing.

New York began as New Netherland, a Dutch colony, until the English seized it in 1664, renaming it after the Duke of York. Neighboring New Jersey, also carved from Dutch territory, was established as a proprietary colony in 1664, later splitting into East and West before reuniting as a royal colony in 1702.

Pennsylvania, founded in 1681 by William Penn as a Quaker refuge, promoted religious tolerance and fair dealings with Native Americans, attracting diverse settlers. Its offshoot, Delaware, originally part of New Sweden, became a separate colony in 1704 under Penn’s charter.

Finally, Georgia, the last of the 13, was founded in 1733 by James Oglethorpe as a buffer against Spanish Florida and a social experiment, initially banning slavery (until 1750) and offering land to debtors.

By the mid-18th century, these colonies—diverse in economy, religion, and governance—had grown distinct identities yet shared grievances against British rule, setting the stage for the American Revolution in 1775. Together, they formed the foundation of the United States.

A Brief History of the Declaration of Independence:

The Declaration of Independence, adopted on July 4, 1776, by the Continental Congress, marked the formal assertion of the 13 American colonies’ break from British rule. Its history reflects the escalating tensions of the mid-18th century and the colonies’ push for self-governance.

By the 1760s, colonial resentment grew due to British policies like the Stamp Act (1765) and Townshend Acts (1767), which imposed taxes without colonial representation in Parliament.

The Boston Massacre (1770) and Boston Tea Party (1773) intensified conflicts, leading to punitive measures like the Intolerable Acts (1774). In response, the First Continental Congress convened in 1774 to coordinate resistance, but war broke out in April 1775 with the battles of Lexington and Concord.

The Second Continental Congress, meeting in May 1775 in Philadelphia, initially sought reconciliation. However, King George III’s rejection of their Olive Branch Petition and his declaration of rebellion shifted sentiment toward independence. On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia proposed a resolution for independence, prompting Congress to appoint a committee—Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston—to draft a document. Jefferson, the primary author, completed the initial draft by late June, drawing on Enlightenment ideas from thinkers like John Locke, emphasizing natural rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

The draft underwent revisions, with Congress debating and editing it—most notably removing a passage condemning slavery—to unify the colonies. On July 2, 1776, Lee’s resolution passed, and on July 4, the final Declaration was adopted, signed initially by John Hancock, Congress president, and later by 56 delegates. Printed copies spread the news, with public readings igniting celebrations.

The Declaration didn’t end the war—it raged until 1783—but it defined the colonies as the United States, justifying their rebellion and rallying support. More than a legal document, it became a symbol of liberty, influencing democratic movements worldwide.

A Brief History of the 13 Original Colonies

The 13 original American colonies were established by European settlers, primarily from England, along the Atlantic coast of North America between the early 17th and mid-18th centuries:

The story begins with Virginia, the first permanent English colony, founded in 1607 at Jamestown. Sponsored by the Virginia Company, settlers faced harsh conditions—disease, starvation, and conflicts with Indigenous peoples—but tobacco cultivation eventually brought economic stability. In 1620, Plymouth Colony (later part of Massachusetts) was established by the Pilgrims, religious separatists seeking freedom from persecution. The nearby Massachusetts Bay Colony, founded in 1630 by Puritans, grew into a theocratic society centered on trade, fishing, and farming.

Maryland emerged in 1634 as a haven for English Catholics, granted by King Charles I to the Calvert family, though it also attracted Protestant settlers. Connecticut (1636) and Rhode Island (1636) splintered from Massachusetts, driven by religious dissenters like Thomas Hooker and Roger Williams, who prioritized individual liberty and separation of church and state.

The Carolinas were chartered in 1663, splitting into North Carolina and South Carolina by 1712. These colonies thrived on rice, indigo, and later slavery, with South Carolina developing a plantation elite. New Hampshire, initially tied to Massachusetts, became a separate colony in 1679, focusing on timber and fishing.

New York began as New Netherland, a Dutch colony, until the English seized it in 1664, renaming it after the Duke of York. Neighboring New Jersey, also carved from Dutch territory, was established as a proprietary colony in 1664, later splitting into East and West before reuniting as a royal colony in 1702.

Pennsylvania, founded in 1681 by William Penn as a Quaker refuge, promoted religious tolerance and fair dealings with Native Americans, attracting diverse settlers. Its offshoot, Delaware, originally part of New Sweden, became a separate colony in 1704 under Penn’s charter.

Finally, Georgia, the last of the 13, was founded in 1733 by James Oglethorpe as a buffer against Spanish Florida and a social experiment, initially banning slavery (until 1750) and offering land to debtors.

By the mid-18th century, these colonies—diverse in economy, religion, and governance—had grown distinct identities yet shared grievances against British rule, setting the stage for the American Revolution in 1775. Together, they formed the foundation of the United States.

A Brief History of the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1775–1783) was a pivotal war where the thirteen American colonies fought for independence from British rule. It began with escalating tensions over taxation and governance, exemplified by acts like the Stamp Act and the Boston Tea Party, leading to armed conflict at Lexington and Concord in 1775. The Declaration of Independence, adopted in 1776, formalized the break from Britain. Under General George Washington, the Continental Army, bolstered by French support after the 1777 Saratoga victory, endured hardships like Valley Forge before triumphing at Yorktown in 1781. The 1783 Treaty of Paris secured U.S. sovereignty, establishing a new nation grounded in revolutionary ideals, though challenges like slavery persisted.

Bailey Anderson, Sr. (1753–1840), born in Stafford County, Virginia, was a Patriot soldier and spy during the Revolution. Relocating to South Carolina’s Ninety Six District, he served in the militia with his father, John, and brothers, Scarlet and Joshua, all of whom perished in the war. Anderson participated in key southern battles—Musgrove’s Mill, Blackstocks, Ninety Six, and the Siege of Augusta—likely spying on British and Loyalist forces in the backcountry. After the war, he migrated to Kentucky (1795), served in its legislature (1800–1802), then moved to Indiana (1805), and finally settled in Texas by 1819. He died in Harrison County, Texas, in 1840, one of 46 Revolutionary War veterans buried there, honored with a Texas Historical Marker.

AUTHORS NOTE: Bailey Sanders, Sr., the owner of this website, Oak Cliff BBQ Company, and the creator of Prime Jerky Fries, is the 10th great grandson of this Revolutionary War patriot and Texas First Families pioneer. Bailey carried on the generations old family tradition of serving America, and is a Cold War and Persian Gulf War veteran. Bailey served first on the USS America (CV-66) conventional aircraft carrier, (at the time moored in Norfolk, Virginia), then on board the USS Von Steuben (SSBN-632) and USS Benjamin Franklin (SSBN-640), both FBM nuclear powered submarines (at the time as moored at Charleston Naval Submarine Base, Charleston, South Carolina), and later the USS Frank Cable (AS-40) submarine tender from April 1984 – December 1993.

A Brief History of the Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence, adopted on July 4, 1776, by the Continental Congress, marked the formal assertion of the 13 American colonies’ break from British rule. Its history reflects the escalating tensions of the mid-18th century and the colonies’ push for self-governance.

By the 1760s, colonial resentment grew due to British policies like the Stamp Act (1765) and Townshend Acts (1767), which imposed taxes without colonial representation in Parliament. The Boston Massacre (1770) and Boston Tea Party (1773) intensified conflicts, leading to punitive measures like the Intolerable Acts (1774). In response, the First Continental Congress convened in 1774 to coordinate resistance, but war broke out in April 1775 with the battles of Lexington and Concord.

The Second Continental Congress, meeting in May 1775 in Philadelphia, initially sought reconciliation. However, King George III’s rejection of their Olive Branch Petition and his declaration of rebellion shifted sentiment toward independence. On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia proposed a resolution for independence, prompting Congress to appoint a committee—Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston—to draft a document. Jefferson, the primary author, completed the initial draft by late June, drawing on Enlightenment ideas from thinkers like John Locke, emphasizing natural rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

The draft underwent revisions, with Congress debating and editing it—most notably removing a passage condemning slavery—to unify the colonies. On July 2, 1776, Lee’s resolution passed, and on July 4, the final Declaration was adopted, signed initially by John Hancock, Congress president, and later by 56 delegates. Printed copies spread the news, with public readings igniting celebrations.

The Declaration didn’t end the war—it raged until 1783—but it defined the colonies as the United States, justifying their rebellion and rallying support. More than a legal document, it became a symbol of liberty, influencing democratic movements worldwide.

A Brief History of the 13 Original Colonies

The 13 original American colonies were established by European settlers, primarily from England, along the Atlantic coast of North America between the early 17th and mid-18th centuries:

The story begins with Virginia, the first permanent English colony, founded in 1607 at Jamestown. Sponsored by the Virginia Company, settlers faced harsh conditions—disease, starvation, and conflicts with Indigenous peoples—but tobacco cultivation eventually brought economic stability. In 1620, Plymouth Colony (later part of Massachusetts) was established by the Pilgrims, religious separatists seeking freedom from persecution. The nearby Massachusetts Bay Colony, founded in 1630 by Puritans, grew into a theocratic society centered on trade, fishing, and farming.

Maryland emerged in 1634 as a haven for English Catholics, granted by King Charles I to the Calvert family, though it also attracted Protestant settlers. Connecticut (1636) and Rhode Island (1636) splintered from Massachusetts, driven by religious dissenters like Thomas Hooker and Roger Williams, who prioritized individual liberty and separation of church and state.

The Carolinas were chartered in 1663, splitting into North Carolina and South Carolina by 1712. These colonies thrived on rice, indigo, and later slavery, with South Carolina developing a plantation elite. New Hampshire, initially tied to Massachusetts, became a separate colony in 1679, focusing on timber and fishing.

New York began as New Netherland, a Dutch colony, until the English seized it in 1664, renaming it after the Duke of York. Neighboring New Jersey, also carved from Dutch territory, was established as a proprietary colony in 1664, later splitting into East and West before reuniting as a royal colony in 1702.

Pennsylvania, founded in 1681 by William Penn as a Quaker refuge, promoted religious tolerance and fair dealings with Native Americans, attracting diverse settlers. Its offshoot, Delaware, originally part of New Sweden, became a separate colony in 1704 under Penn’s charter.

Finally, Georgia, the last of the 13, was founded in 1733 by James Oglethorpe as a buffer against Spanish Florida and a social experiment, initially banning slavery (until 1750) and offering land to debtors.

By the mid-18th century, these colonies—diverse in economy, religion, and governance—had grown distinct identities yet shared grievances against British rule, setting the stage for the American Revolution in 1775. Together, they formed the foundation of the United States.

A Brief History of the Declaration of Independence:

The Declaration of Independence, adopted on July 4, 1776, by the Continental Congress, marked the formal assertion of the 13 American colonies’ break from British rule. Its history reflects the escalating tensions of the mid-18th century and the colonies’ push for self-governance.

By the 1760s, colonial resentment grew due to British policies like the Stamp Act (1765) and Townshend Acts (1767), which imposed taxes without colonial representation in Parliament.

The Boston Massacre (1770) and Boston Tea Party (1773) intensified conflicts, leading to punitive measures like the Intolerable Acts (1774). In response, the First Continental Congress convened in 1774 to coordinate resistance, but war broke out in April 1775 with the battles of Lexington and Concord.

The Second Continental Congress, meeting in May 1775 in Philadelphia, initially sought reconciliation. However, King George III’s rejection of their Olive Branch Petition and his declaration of rebellion shifted sentiment toward independence. On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia proposed a resolution for independence, prompting Congress to appoint a committee—Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston—to draft a document. Jefferson, the primary author, completed the initial draft by late June, drawing on Enlightenment ideas from thinkers like John Locke, emphasizing natural rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

The draft underwent revisions, with Congress debating and editing it—most notably removing a passage condemning slavery—to unify the colonies. On July 2, 1776, Lee’s resolution passed, and on July 4, the final Declaration was adopted, signed initially by John Hancock, Congress president, and later by 56 delegates. Printed copies spread the news, with public readings igniting celebrations.

The Declaration didn’t end the war—it raged until 1783—but it defined the colonies as the United States, justifying their rebellion and rallying support. More than a legal document, it became a symbol of liberty, influencing democratic movements worldwide.